The Weight of Books: Rethinking My Literary Footprint

More than a decade ago, long before the advent of AI, back in that era of technological baby steps, my wife suggested that I give up buying printed books.

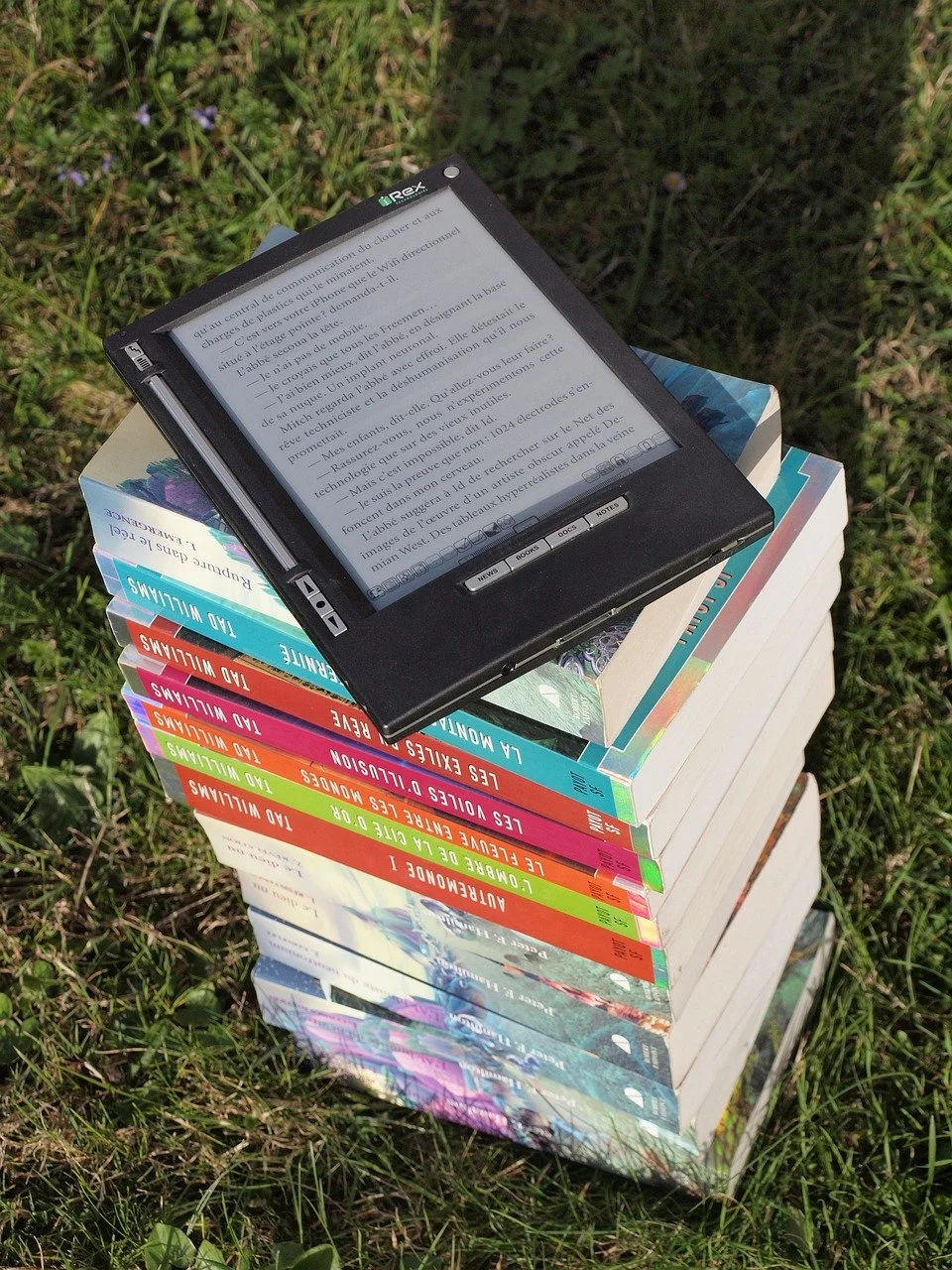

The new Amazon Kindle had flooded the reading world like a literary tsunami. In her eyes, the advancement freed book-buyers like me from the living hell of coping with all those books-already-read, the clutter that bulged from shelves or formed teetering piles on the living room floor for the cat to topple.

Electronic readers were the future, she insisted, and I needed to get with the program. I could carry a slender device not much bigger than my hand, containing hundreds of pre-paid selections that I could simply erase after reading, or not.

Get rid of my treasured books? Just the thought was outright heresy.

“Over my dead body,” I protested.

And here’s why.

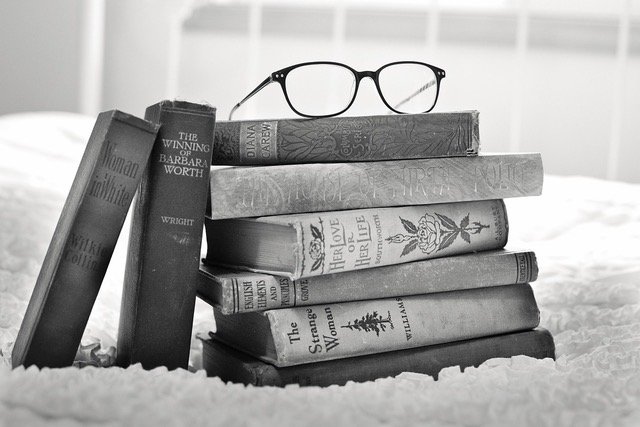

I liked my books, loved them, even cherished them. For years, I had kept a home library—several wall-spanning shelves in my living room and office—that I saw as critical mass for a thinking man of the modern world, especially for a working journalist and former college English major. My reading habits have long leaned toward nonfiction and, collectively, my books became a road map of my intellectual discoveries and misadventures.

“This is what I care about,” they said. “This is what I have tried to understand.”

As a collection, my books reflected something about the discerning adult I had become. I liked the fact that visitors commented on the breadth and depth of my library, but more importantly, I liked having all these ideas at my fingertips. While most of the array consisted of previously read volumes, I also reserved several shelves for newly purchased books that I couldn’t wait to delve into.

Each time I finished one nonfiction title, even if it was at 3 a.m., I would immediately return it to the shelves and then select my next book—a personal passing of the torch, if you will. I’d peruse the back cover and testimonials and then set it on my night table, ready to tap its contents when the mood struck.

I was knee-deep in the technology of the day. Each morning, I held the daily newspaper in my hands. I had my magazines delivered to the house. And my books were made of bound paper, purchased from scrappy independent booksellers, not Barnes & Noble, just like they should be.

Call it a literary fetish, but I liked to hold my books in my grasp. I liked the smell of the paper and the ink. I liked my books fresh off the presses, just like I liked my newspapers. A book in the hand, I told my wife, was better than a thousand online imitators.

I was not going to give in to the demands of technology. No way, no how.

That is, until now.

A lot has changed since I lived in suburban Las Vegas, working as a newspaper national correspondent. My house has a separate casita that I used as an office with wall-to-wall books. The more chock-full and disheveled my shelves became, the more I felt like that old curmudgeon who had seen the world and held onto these priceless little mementos of the journey.

I left full-time newspaper work in 2015. Then, during COVID, after a few years of freelancing, I rejoined my wife just outside San Francisco, where she had carried on her own career while I indulged in mine.

We upgraded from her cramped one-bedroom condo to a two-bedroom unit in the same complex, where I set up my work office. Still, space came at a premium. While my Vegas manse measured some 2,500 square feet, the new place was less than 1,000.

Suddenly, there wasn’t room for bookshelves. I’d left my collection in Vegas, stored in the casita, awaiting the time when I decide to re-embrace it.

Nowadays, when I return from Green Apple Books, my favorite San Francisco literary haunt, or rip open my latest Amazon book purchase, my wife takes notice.

“Where’s that gonna go?” she demands.

I don’t know what to tell her. Now, when I finish my latest narrative, there’s no logical place to store it. I stash books in closets, under the couch and under the bed. Rather than proudly displaying my already-read prizes on trophy shelves, I resort to hiding them.

Like sins, or mistakes. It just isn’t me.

I have a friend who once kept a considerable collection of Civil War memorabilia all over his bachelor pad. When he got married, his new wife confined his habit to one small bedroom. That’s how my wife is with books; they’re my passion, not hers. They’re consigned to one room, best kept out of sight, not spread throughout the condo like so much intellectual wreckage.

To say the least, this new space conundrum cramps my style. I have turned into a guilty book buyer, pausing in the bookstore aisles, burying the finished books I do buy like corpses in the backyard, while waiting for the police to come and put me in handcuffs.

Once again, my wife has provided the solution.

The other night, I was telling her about a fascinating book by Hampton Sides I’d just finished, called Hellhound on His Trail, about the international manhunt for Martin Luther King assassin James Earl Ray.

She didn’t share my sense of wonderment.

“We need to talk,” she said.

It was time, she insisted, that I take ownership of my literary footprint, to reconsider the emotional weight of all my books.

The world is changing, she said. Electronic reading is no longer dismissed like online dating in the old days. Especially in big cities, where space is precious, it has become more of the cultural norm.

Books, she reasoned, are merely reading experiences, not family heirlooms. Keeping used books because “books are sacred” is just delayed disposal. If books are like conversations, I don’t need of a record of every sit-down fireside chat I’ve ever had. I wasn’t giving up my reading habit; I was giving up clutter, no longer allowing my living space to be overrun by paper.

And you know what? This time I listened.

If I eventually sell my Las Vegas house to scale down my life, my mothballed library will be in peril. Putting my books in storage seems like delaying the inevitable. For a book lover, I’m in a tough spot. And it’s the devaluing of my lifelong stock of literary trade that troubles me the most.

These days, nobody seems to want used books, unless they’re first editions signed by the author. Libraries curate; they don’t warehouse. Used bookstores need resale certainty. The Salvation Army might take a book or two, but not many hundreds.

The market assigns these books zero value, which I find unfair and even insulting. You can’t give them away. I might as well load my Vegas collection into a U-Haul van, drive out to the desert at midnight, and bury them all in a huge pit next to Jimmy Hoffa’s unmarked grave.

A generational transition is afoot. And it’s not just books. I switched to reading newspapers online years ago, but have recently noticed that my dogeared magazines end up in unsightly piles. And so have I changed my subscriptions to The Atlantic, Harper’s and The New Yorker to digital only.

Already, I feel a sense of relief, like a burden has been lifted.

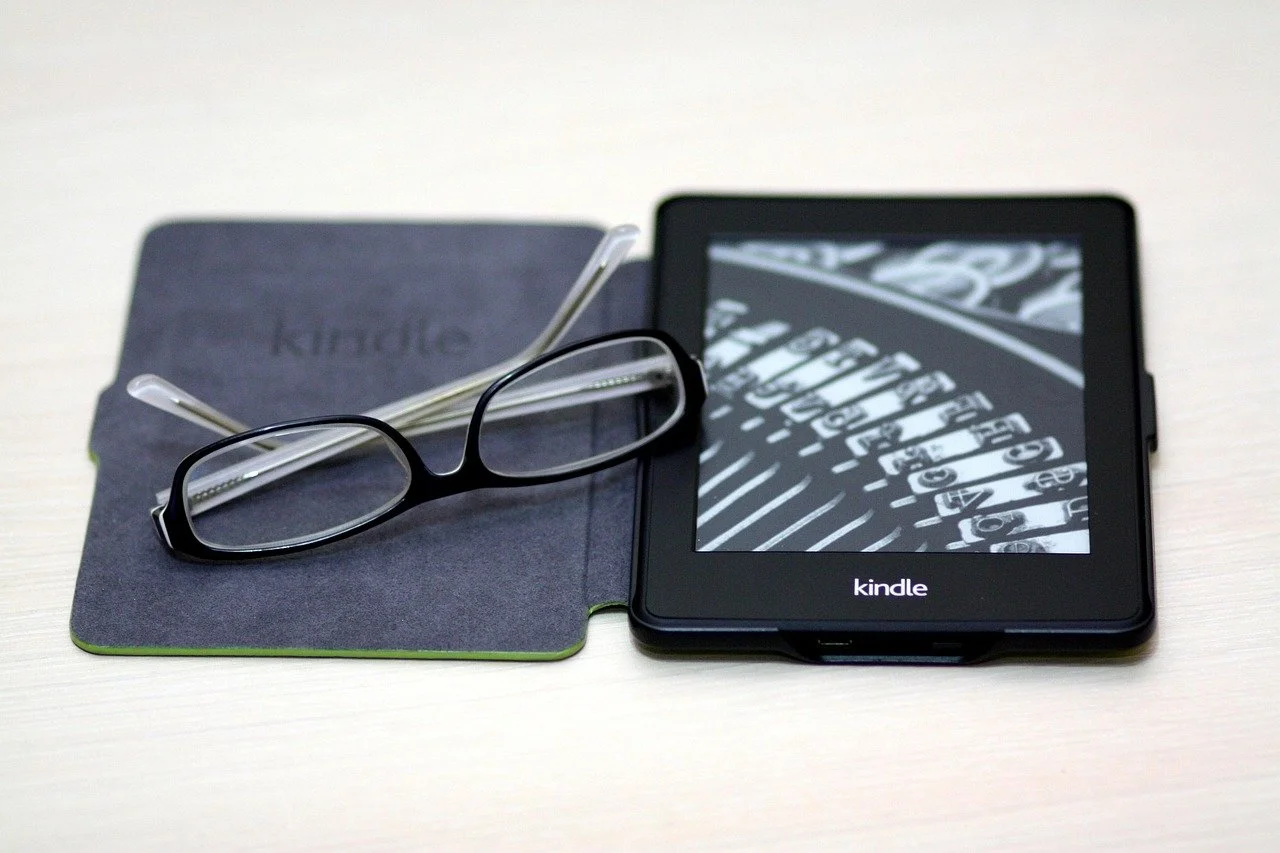

Then, the other day, at my wife’s urging, I bought a new Amazon Kindle Paperwhite, a nifty cover, and a charging station for about 300 bucks. I quickly downloaded my first book—another nonfiction work by Hampton Sides called Ghost Soldiers, about a top-secret mission to rescue World War II prisoners from a Japanese camp in the Philippines.

Right away, I was amazed at how small the device is. I can put it in my pocket. I enlarged the letter font and employed the warm amber-light function to ease the burden on my tired, aging eyes.

At first, the reading experience was a bit jarring. I tap the screen instead of turning the page. I’m also used to flipping back pages to reorient myself with the plot, and this is different on the Kindle.

But I’m not giving up. My wife says that after two weeks, I won’t miss paper in the least. Of course, I’m not completely forsaking bound books. I have several in my collection I’ve yet to get to. I also have my Vegas stash to deal with, eventually.

Still, I feel like I’ve turned a page on an old habit and embraced the future of my beloved pastime. And I’ve learned a lesson about the foibles of becoming too attached to material things. Sometimes, you’ve just got to let go of the things you think you need.

As my wife and I plan a possible move abroad, I don’t anticipate scrambling to find expensive English-language editions in some foreign culture. I’ll have my Kindle, and that gives me a sense of peace.

It’s like finishing a good book.